PESP Webinar: Private Equity’s Impact on Education

January 17, 2023

Private equity firms and the companies they own come in contact with students, teachers, administrators, and families in a variety of ways in the education sector. With the power to create educational content and administer tests, hire school staff, manage student data, and own for-profit schools comes the great responsibility of acting in the best interest of students, not profits. A new report from the Private Equity Stakeholder Project explores who ultimately decides what students learn in the classroom, and what happens when public funding of education begins to look more like a monopoly, benefitting Wall Street investors.

PESP hosted a webinar on December 1 featuring PESP Research & Campaign Coordinator Azani Creeks, Independent Media Institute journalist Jeff Bryant, former Center for Democracy and Technology researcher Hugh Grant-Chapman, and Care that Works senior researcher Sarah Jimenez.Video of the webinar is available here.

Private equity-owned companies are major players in curriculum development and test administration in the US, providing content for students in classrooms and at home. Portfolio companies of these private equity firms not only create platforms that make learning possible but also develop and administer the instruction itself. As districts across the U.S. face teacher shortages, edtech companies are stepping in to provide platforms for supplemental or full instruction. Furthermore, several of the largest standardized testing providers are owned by private equity firms, bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars through state-wide testing contracts.

Hugh Grant-Chapman shared how monitoring software is being used to discipline students more often than to increase student safety. He spoke about how teachers are bearing a large amount of responsibility for monitoring this software but receive little training on it, creating a huge burden on teachers.

Alarmingly, Grant-Chapman said that the monitoring software is active after hours or on weekends, equating to 24-hour tracking and surveillance of students. This student monitoring puts students at increased risk for contact with law enforcement. Stakeholders, including families, students and teachers have indicated major knowledge gaps on how this software actually works and what its implications are.

With private equity-ownership of education, curriculum is down to the bare minimum. This has meant no textbooks, few learning materials, libraries stripped bare, and cutting of programs like after-school services. Very few things outside of the core curriculum were available (i.e. band or drama). The education being offered is not well-rounded, and instead focused on test preparation, according to Grant-Chapman.

Grant-Chapman also spoke about how teacher-turnover always increased when private equity bought education institutions. There became an emphasis on pushing young teachers through the school to keep wages low, often no support staff for ESL or special education; outsourcing of services increases; and less transparent school operations.

Private equity firms and the companies they own have promised to improve educational outcomes for struggling individual students and schools through new technology, personalized learning strategies, and resources for staffing and administration, but there is no conclusive data showing that school funding is better spent at private-equity owned companies than staying within the district. Private equity firms have acquired educational institutions themselves such as early childhood education centers, private and charter K-12 schools, and for-profit colleges. Overall, outcomes for higher ed students at for-profit institutions are worse than at public or private non-profit schools. Furthermore, for-profit colleges have exacerbated racial disparities and educational outcomes.

Jeff Bryant discussed an example in Cleveland, where private equity has taken over dozens of charter schools. In his research of the trend, Bryant found that schools acquired by private equity firms “would strip down resources and facilities to the bare bones… the curriculum and program offerings are reduced to the bare minimum.” Bryant also noted that teacher turnover increased when private equity firms took over Ohio schools, making it difficult for students and families to build relationships with staff and access the resources they need. He concluded with how private equity ownership of schools was of no benefit to the school children of Cleveland.

Sarah Jimenez revealed how private equity’s cost-cutting strategies impact childcare workers. Workers at for-profit childcare centers face the highest turnover rate in the industry, are overworked due to understaffing, and have no union protections. Jimenez highlighted the opportunities for union solidarity in the fight for better quality education and working conditions for childcare workers; for instance, public school teachers can be in solidarity with childcare workers while fighting for childcare benefits in their contracts. This opens up space for us to support and encourage organizing, especially when private equity buys up our education systems.

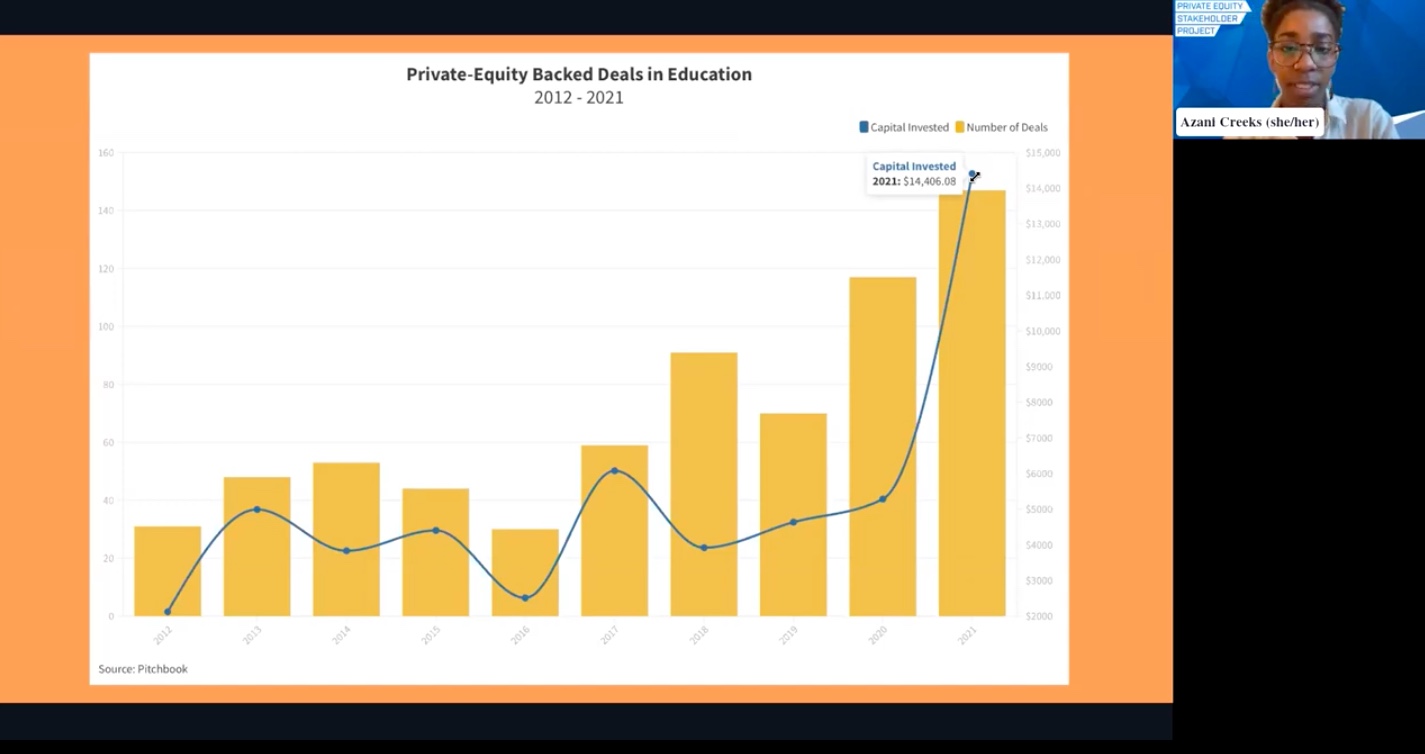

In 2021, private equity firms completed a record number of deals in the education sector, following a trend that has seen increases each year since 2007. The impact of private equity on our country’s education systems deserves scrutiny.